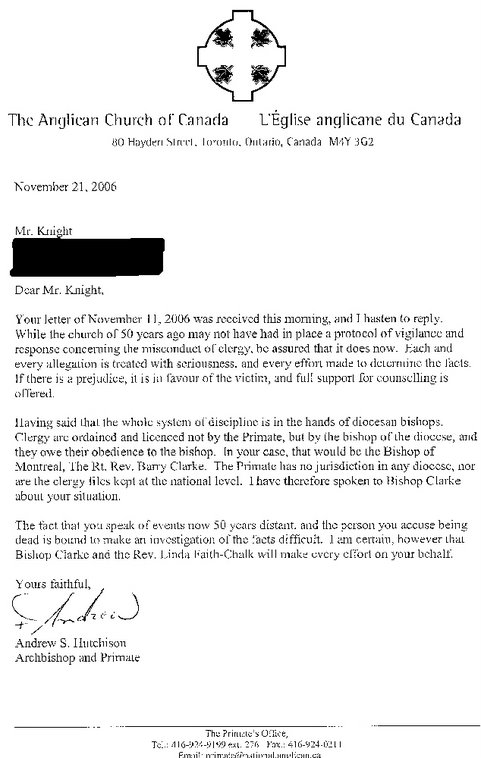

Former Toledo Police Detective Bill Gray shows the report he filed against the Rev. Robert Thomas in 1984 for molesting a teen boy in the Southwyck Shopping Center.

Former Toledo Police Detective Bill Gray shows the report he filed against the Rev. Robert Thomas in 1984 for molesting a teen boy in the Southwyck Shopping Center. _______________________________

Shame, Sin and Secrets

By Michael D. Sallah and David Yonke

Toledo Blade

December 1, 2002

On a wintry Sunday afternoon, Toledo policeman William Gray barged into a men’s room in Southwyck Shopping Center, surprising a 53-year-old man and a 16-year-old boy engaged in sex.

After frisking the man and slapping handcuffs on him, the veteran policeman realized he had crossed a sacred line: He was arresting a priest.

The year was 1984, and the man escorted to jail in white jeans and a muscle shirt had just celebrated Mass that morning as pastor at Our Lady of Perpetual Help Church in Toledo.

But the career of the Rev. Robert Thomas was far from over.

In the following years, his arrest reports disappeared, his record was expunged, and he was sent by the diocese to four more parishes, including three in Arizona. It wasn’t until this spring that the Tucson diocese says it learned of his arrest from a Blade reporter, prompting the priest’s immediate suspension from the ministry 17 1/2 years after his crime.

Of all the accusations of sexual abuse in the Toledo diocese, the case stands out for one reason: It wasn’t kept secret.

Indeed, for generations, the diocese engaged in a practice of covering up the rapes and sexual abuse of children by those sworn to guide them: priests and teachers, a Blade investigation shows.

In every decade since the 1950s, there have been at least two examples of priests or others entrusted with the care of minors accused of forcing the youngsters into sex acts, but the diocese failed to notify police.

Instead, the abusers were moved to new churches or schools sometimes after therapy and in some cases, only to rape and abuse again.

In a rare look at the diocese’s inner workings, The Blade reviewed more than 2,000 court and church records of 24 child-abuse cases involving priests and church workers from 1960 to 1994.

More than 30 victims were interviewed, and in some cases, provided reporters with secret archives of their cases given to them by the diocese.

The investigation found:

Only three priests were ever criminally charged though at least 12 admitted to sexually abusing children. In the three arrests, the police not the church initiated the investigations.

Some youngsters were forced to perform oral sex, others were raped, and still others were disrobed and fondled sometimes repeatedly in the sanctuary of schools, churches, and rectories.

In many cases, not only were police kept in the dark, but so were parishioners. At least 12 times the diocese moved accused abusers to other parishes without telling the new flocks of the priests’ past abuses. In two cases this year, congregations were misled about their priests’ abuses until their actions were revealed by the media.

In at least eight cases, diocesan lawyers struck confidential out-of-court settlements with accusers silencing victims for years.

"The children were betrayed," said Judy Laddaga, a former Waterville mother who tried to warn the diocese about a troubled priest in 1985. "Where was the heart of the shepherd? The church is supposed to protect its flock, especially the ones who need protection the most."

Toledo diocesan leaders admit that when priests were accused of sex crimes, the transgressions were rarely if ever reported.

Those who abused often were considered fallen clerics instead of criminals and were sent to treatment centers or monasteries, said Bishop James Hoffman, leader of the diocese since 1981.

But he and others insist that no known incidents have occurred since the diocese adopted a sex-abuse policy in 1995 and that any future accusations will be reported to law enforcement officials.

"If I knew then what I know today, I’m sure I would have handled some things differently," said Bishop Hoffman in a recent interview, adding that the church has gained a greater understanding of abuse during the last two decades.

But even after the 1995 policy was enacted, the diocese has failed in some instances to uphold its own guidelines.

In one case, an accused abuser was allowed to participate in two youth events as recently as last year including an overnight trip with teens.

In another incident, the diocese failed to remove a molester from ministry until his role on a church tribunal was revealed in August.

Though church leaders rejected The Blade’s requests to open sex-abuse records, they agreed in August to allow the Lucas County prosecutor’s office to review the archives.

CRISIS in TOLEDO

As the abuse by clerics scandal unfolds nationally - first in Boston and now in 116 dioceses across America the Toledo diocese has undergone its own crisis, with its own disturbing cases surfacing after being buried in the archives of the institution for decades.

It is a story of victims who had lived in silence in some cases for five decades until the church scandal broke this year.

It is about priests who often denied the accusations - and in a half-dozen cases, threatened victims not to talk.

It is about years of special treatment for clerics, and in at least two cases, law enforcement turning a blind eye to abuse.

The crisis unfolds as the diocese reaches its 92nd year, growing from a group of rural churches and neighborhood parishes to a social powerhouse that has built hospitals, schools, and soup kitchens more than any other denomination.

Of all the priests who have served the diocese, only a fraction ever have been accused of sexual misconduct.

But those who have crossed the line and church leaders who covered up their crimes have created a new legacy that has shaken the institution’s foundation.

"We’re in a genuine crisis," said Toledo priest Jim Bacik, one of the diocese’s leading theologians. "I don’t think we knew the depth and the complexity of the problem until now."

To this day, few people beside church leaders know the extent of abuse against children by clerics in the diocese a sprawling 19-county area with 162 parishes ministering to 322,938 Catholics.

Even less is known about cases of Toledo priests who are members of religious orders like the Jesuits and the Oblates of St. Francis de Sales who answer to their own superiors, while requiring diocesan approval to work here.

Two of the worst offenders, Chet Warren and James Rapp, were Oblates, whose regional headquarters is in Toledo.

While The Blade reviewed the cases of 18 priests and six diocesan workers accused of sexually abusing children since 1960, a local support group Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests counts 36 local priests accused of sex crimes against youngsters since 1947 the number based on its own interviews with victims.

And those are only the ones that are known.

The case of Richard Trepinski shows how a church employee preyed on children and managed to get away with his crimes for years.

When the longtime choir director was arrested in Florida a decade ago on 99 child sex abuse charges, he confessed he had been molesting children for decades, going back to his days in Toledo, where he served 21 years at Christ the King. But Toledo diocesan officials say they never knew.

Studies of clerical sex crimes show fewer than 15 percent of victims ever step forward to talk about their pain citing fear and embarrassment as the overriding reasons.

Emboldened by other victims stepping forward, William Claar said it took 28 years for him to speak publicly about his anguish.

"I thought I was the only one. I was so alone," said Mr. Claar, 43, who claims in a lawsuit that the Rev. Bernard Kokocinski raped him in a Fremont rectory in 1975. "I lived with the guilt and the shame for so long. I’ll never be anonymous about this again."

SEX SCANDAL EXPLODED

As the Catholic sex scandal exploded in other cities across the nation, Toledo was quiet.

In the first four months of this year, 176 priests were removed from ministry for sexual misconduct with children, but none in northwest Ohio.

Then came the case of Leo Welch.

The former Toledo priest dropped what one lawyer called a "bomb" on the local diocese this summer that exposed patterns of cover-up and secrecy from the 1960s that rivaled the most chilling stories of priestly abuse.

His stark admissions to The Blade in June of sexually abusing boys from Immaculate Conception Church in Bellevue marked the first time a former Toledo priest talked to a reporter about such crimes. But there was more.

He confessed that after he was caught in 1961, church leaders never called police, instead ordering him to pack his bags and leave immediately.

"I was told to go stay with my parents in Oregon [Ohio]," the former priest said.

Within days, the parents of a victim went to Bellevue prosecutor Charles Sliter a parish member who failed to notify police, according to law enforcement officials in Bellevue and Lucas County.

Within three months, Father Welch was quietly reassigned to Toledo’s Christ the King parish, 57 miles away - and the new congregation was never told of his problems.

Two of his victims eventually came forward. George Keller, 53, and Harold Lee, 51, drew national attention to the diocese with a lawsuit filed by two of the nation’s most recognized practitioners of law dealing with clergy abuse: Jeff Anderson and Bill Crosby.

The victims talked about the four dozen altar boys taken to Father Welch’s cottage near Toledo between 1956 and 1961 a children’s fantasy world, with a pond, a go-cart track, and a boat.

"We would all be coaxed into his bedroom, one by one," says Mr. Keller, a married father of four.

After some playful wrestling with the boys ages 9 through 13 some were penetrated and forced into oral sex, they said.

Like other victims across the nation, people ranging in age from 28 to 67 began to step forward in the Toledo area to talk about their own childhood stories of abuse by priests and other church leaders.

It was like the floodgates opened," said Claudia Vercellotti, local coordinator of SNAP. "People felt they could now talk without being afraid."

In six of the 24 cases reviewed by The Blade, priests intimidated their victims from ever talking, keeping them in silence, records and interviews show.

A 55-year-old Michigan woman said it took her 38 years before she raised the courage to call the diocese this summer.

In the darkness of an office at Toledo’s Central Catholic High School in 1964, she said she was warned by the Rev. Thomas Beauregard that she would "go to hell" if she ever divulged what took place one night.

The priest, now 75, who has admitted to Bishop Hoffman that he sexually abused teenage girls, told her to disrobe before fondling her during a counseling session. She said she went to the priest because she was depressed.

"I was young. It scared me to death," she said in an interview.

Another woman, now 54, said Father Beauregard ordered her to sign a "legal agreement" saying she would never divulge their sessions in the rectory of Little Flower Church in 1965.

"He said he was writing a book and didn’t want me saying anything," said the woman, who took her complaint to the bishop in 1994.

Father Beauregard did not return phone messages. He was removed from ministry in September - eight years after he admitted to his abuse.

SPECIAL TREATMENT

In years past, society gave special treatment to priests - free meals, golf, and cab fares.

Sometimes those favors extended to the justice system.

For the Rev. Alexander Pinter, a national figure in the Hungarian freedom movement in the 1950s, it was his collar that kept him out of jail in a cover-up that involved the diocese - and police.

A popular priest in East Toledo’s Hungarian community in the 1950s, the pastor of St. Stephen parish was accused of raping and abusing altar boys.

But when parishioners went to police in 1960, he was never arrested.

Instead, the 41-year-old cleric was allowed to quietly leave for Canada in a case that still riles members of the close-knit parish.

During his four years as pastor starting in 1956, he was accused of driving young boys to a cottage in eastern Lucas County, where he would rape them in the privacy of his bedroom, according to two retired police officers.

Gene Fodor, 69, who grew up in the neighborhood, said his police supervisors met with then-Bishop George Rehring and gave an ultimatum: Get rid of Father Pinter, or the priest would be arrested.

A native of Hungary, the gregarious priest captured headlines when he helped refugees fleeing his country to settle safely in America.

"It was becoming a scandal, but they did not want to arrest him," said Mr. Fodor, who retired from the force in 1987. Instead the cleric was sent to a treatment facility in Canada in July, 1960.

One longtime parishioner, Irene Hornyak, said it would have been impossible for Father Pinter to come back. "Everyone in the neighborhood knew what he was doing," she said. "They needed to get him out."

He eventually left Canada and taught in several U.S. seminaries before settling in Louisiana as a parish priest in 1974. He died four years later in Westwego, La., at 59 his Toledo secrets never made public.

The official history of St Stephen parish gives a cryptic account of his exit, saying only that "there was some controversy concerning his departure."

The case typified an era of special treatment by police in Toledo and nationwide even when allegations were taken to law enforcement. But by the 1980s, that appeared to be waning.

Toledo police officer William Gray was a witness to that trend. After arresting Father Thomas of Our Lady of Perpetual Help Church and a teenage boy in a Southwyck restroom in 1984, the officer said he received calls from fellow police and diocesan officials.

"I was under a lot of pressure for arresting a priest," he said. "But I wasn’t going to back down. He broke the law. They kept saying, ‘Do you know who you arrested?’ and ‘Why did you have to do that?’’’

Father Thomas was convicted before then-Municipal Court Judge William Skow, but within a year, the arrest and sentencing reports were expunged. Mr. Gray, now 58, kept a copy of the arrest records before retiring in 1996.

"I knew someday those reports would be gone," he said.

A CHILLING NOTE

In 1986, a sex-disorder clinic director wrote a chilling note about Father James Rapp: Don’t leave this priest alone with children.

For years, the 46-year-old priest of the Oblates of St. Francis de Sales said he tried to stop molesting teenage boys, and for years, he couldn’t help himself, court records show.

After he was caught abusing two boys in Jackson, Mich. 75 miles north of Toledo he was sent to a Maryland clinic in 1986.

But the diagnosis of ephebophilia, a sexual attraction to adolescent boys, soon would be forgotten. And in early 1991, the priest’s Toledo superiors sent him to a remote parish in Oklahoma.

In the following years, the cleric went on a sexual rampage, raping and molesting at least three more boys in a case that led to a lawsuit and a settlement of $5 million, the second-largest ever paid to a victim of a priest.

Lawyers for the victims laid much of the blame on his Toledo superiors for failing to follow the advice of the doctor they hired a decade earlier. The ex-priest, now 61, was sentenced to 40 years in prison in 1999.

The case has been cited by lawyers across the country as an example of church supervisors not heeding the warnings.

Decade after decade, church leaders in Toledo failed to act on strong evidence that some of their own priests were endangering children.

In nearly half of the 24 sexual misconduct cases reviewed by The Blade, diocesan officials sent accused priests to new assignments, and in some cases, new victims.

Consider the case of Dennis Gray.

The diocese was warned repeatedly in the 1980s that the charismatic priest was troubled, potentially dangerous, and was taking teenage boys to his cottage in Michigan.

In September, 1985, Maumee police investigated a report of an altar boy who said Father Gray cornered him in the sacristy of St. Joseph Church, gripped his hand in a "nerve hold," and ordered him to "submit to punishment."

In addition, the police report warned that Father Gray had "taken kids to a cottage in Michigan" with another priest who had been arrested previously for gross sexual indecency with a male.

A local psychiatrist urged the diocese to get psychiatric help for Father Gray, according to a Feb. 6, 1986, letter.

John "Archie" Thomas, Catholic school superintendent at the time and one of the diocese’s highest-ranking officials, ordered an investigation, says a retired priest and retired Toledo detective who was consulted in the case. But the diocese’s findings never were made public.

By the next year, Father Gray took a leave of absence from Central Catholic High School, where he taught religion. In February, 1987, he left the ministry.

He went on to work with a positive reference from Auxiliary Bishop Robert Donnelly as a Lucas County probation officer and Maumee Youth Camp counselor before joining Toledo public schools as a dean of boys in 1990.

In an interview in September, Mr. Gray denied the abuse accusations, saying they were "all hearsay," but diocesan records state he admitted to past child abuse in 1995, eight years after leaving the priesthood.

In his own letter to victim Matt Simon in 1996 10 years after the abuse Mr. Gray, wrote: "Please forgive me. I have been in therapy for the past year and a half, learning to deal with the demons of the past."

In the last two months, nine men have filed lawsuits saying they were raped and abused by then-Father Gray between 1975 and 1987 - with two former students saying they may have been spared had the diocese heeded earlier warnings.

"I think about this all the time. If the diocese had only listened to people," said a 32-year-old victim who claimed in a September lawsuit he was raped repeatedly by then-Father Gray between 1984 and 1987.

The victim, now a Toledo businessman, said the priest once tried to silence him by pinning him against a school wall, holding a pen to this throat, and warning him not to talk about activities at the cottage.

And then there’s the case of Richard Liston, a troubled priest accused of raping a teenager from St. Paul parish in Norwalk in 1978.

The diocese transferred the cleric to St. Rose in Perrysburg, never telling that congregation about his past, and eventually to the former St. Ann parish in Toledo as an administrator, where he would not have contact with children.

It wasn’t until a Toledo police investigation in 1985 into the priest’s financial interest in two gay bars did his past come to light, according to a retired police officer and the Rev. Michael Billian, diocesan chancellor.

The diocese sent him to a treatment center in Virginia, but he walked away.

SNAP representatives say the secret transfer of Father Liston, who died in January, 1994, is a glaring example of how church leaders moved troubled priests around, "exposing other kids," says Ms. Vercellotti. "They were playing a dangerous game."

Another example is Herbert Richey, Jr.

After a series of confidential settlements with the families of young male victims, the priest was forced from the ministry by the Toledo diocese in 1992, records show.

Bishop Hoffman said there were settlements over sex-abuse allegations involving children but declined to talk about the former cleric, who served in parishes in Findlay, Sandusky, Mansfield, Vermilion, and Wakeman before leaving the ministry on May, 31, 1992.

Several years later, he turned up as music director and organist at St. Michael the Archangel parish in Toledo, without the congregation being made aware of his past. He is now a substitute organist in the Detroit archdiocese, records show.

HIS FINAL SERMON

In his final sermon five months ago, the Rev. John Shiffler told his flock that an "indiscretion," an "inappropriate touch" from 18 years ago was the sole reason he could no longer be their priest.

"It wasn’t one of those horror stories of abuse," the 50-year-old cleric told his parishioners at Our Lady of Fatima Church, in Lyons, Ohio.

He was being pulled from ministry, and the person overseeing the priest’s last sermon to his flock that July day was the second-most powerful cleric in the diocese Robert Donnelly, the auxiliary bishop.

Moved by Father Shiffler’s words, the parish rallied around their priest, raising money for his living expenses and petitioning Bishop Hoffman to rescind his decision.

"Our hearts went out to him," recalls a parishioner.

Ten weeks later, parishioners were stunned to learn that their priest had lied to them.

Father Shiffler was being removed because he had sexually abused two teenage boys when he was a teacher at Central Catholic High School in the late 1980s with one of the secret sessions in a parish rectory.

Adding to the parishioners’ sense of betrayal was that Bishop Donnelly sat in the church that day, never correcting his priest.

While Toledo diocesan leaders say their 1995 policy has transformed the way the local church responds to sexual-abuse, inconsistencies and oversights abound in the way it’s enforced.

For example, Terry Steinbauer was forced to resign in 1996 as the diocese’s director of youth ministries and banned from youth events after four women accused him of sex abuse when they were teenagers, diocesan records show.

But as recently as last year, he was still joining in church retreats for teens.

In fact, the 46-year-old man stayed overnight with teenage girls and boys on a trip to southern Ohio organized by All Saints Church in Rossford in the summer of 2001. Bishop Hoffman since has apologized for the lapse.

In another case, Father Beauregard, who admitted in 1994 to sexually abusing teenage girls, was allowed to remain in ministry eight years after the first complaint.

Not until the media reported on his case in August did the diocese remove the 75-year-old priest from ministry.

His last job: sitting on a tribunal and deciding whether couples can be granted annulments based on intimate details of their lives.

There’s also the controversy of the Rev. Larry Scharf. When two men went to the diocese in March, saying they were sexually abused as teenagers by the priest in 1976 and 1981, he admitted to the accusations.

But instead of telling the priest’s congregation at St. Joseph parish in Monroeville the real reasons for his sudden departure, church leaders said only he left for "health reasons."

Three months later, after the media revealed the abuse, the bishop announced the priest’s sex offenses.

Despite disagreements, victims and church leaders agree on the obvious goal of preventing more abuses. But questions abound over the necessary steps that need to be taken.

Local SNAP leaders are calling for public disclosure of the church’s abuse archives. So far the diocese has only agreed to open some records to local prosecutors, and that action was delayed two months.

Lawyers who have sued dioceses across the country believe the 13 sex-abuse suits filed this year against the Toledo diocese ultimately will force church leaders to surrender secret files.

Since 1981, the diocese has spent $469,584.02 to cover "settlements, pastoral care, and legal fees" in child-abuse cases, with the money coming from a self-insurance fund, Bishop Hoffman said. But with legal pressures mounting, costs are bound to rise significantly in the coming years.

Court actions and public campaigns have heightened tensions between victims’ advocates and church supporters.

When SNAP founder Barbara Blaine, a Toledo native and abuse victim, was to appear Sept. 5 at the University of Toledo law school, the Rev. Thomas Quinn, diocesan communications director, told a Blade reporter: "Where do we place the bombs? And you can quote me on that."

Father Quinn’s dark humor aside, Bishop Hoffman, 70, said the controversy has been the most difficult of his 21-year term.

"I don’t think there’s any question," he said.

A member of the bishop’s nine-year-old study committee on sex abuse said the diocese was part of a culture that fell short in protecting those on whom the church’s future rested: children

"There’s no question our diocese could have done a better job," said Dr. Bernard Cullen, a clinical professor of pediatrics of Medical College of Ohio. "I think some of the leaders would say that if not for the lawsuits."

_____________________________________________

PART 2: Believers Betrayed

Special Report

Believers Betrayed

Victims lived in silence for years until the truth began to be uncovered

By Michael D. Sallah and David Yonke

Toledo Blade

December 1, 2002

At the Claar home in Fremont, there was always a seat at the table for Father Bernard Kokocinski. Sunday dinners. Birthday parties. Bike trips along the leafy neighborhood streets that lead to historic St. Joseph parish.

"He was close to everyone," says William Claar, one of three children of Buddy and Louise Claar.

William Claar, 43, with a teenage photo of himself, says he was molested repeatedly. Photo by Associated Press.

But there was another side to the charismatic priest, who earned the trust of the staunch Catholic family in the working-class town.

In the privacy of the rectory in 1975, he repeatedly raped and molested the young boy in sessions that went on for a year, a lawsuit claims.

For most of his life, the youngster lived in shame, transferring to another school and eventually joining the Air Force.

"I never told my parents. I never told anyone," he says. "He was like a member of the family. I didn’t think anyone would believe me."

But last month, encouraged by victims’ stories of clerical abuse, he surprised his family by talking about his anguish and then taking another step: He sued the priest in Lucas County Common Pleas Court on Oct. 18.

Two days later, Mr. Claar’s younger brother, Scott, called with more shocking news: His big brother wasn’t alone.

He too had been repeatedly molested by Father Kokocinski, and he too carried the shame for years, he says.

"He was crying when he called me," says William Claar, now 43. "It all came out - everything."

The brothers soon discovered the man they knew as Father Bernie had a troubled past: arrests on charges of sexual imposition in 1972, soliciting an undercover policeman for sex in 1979, and indecent exposure in 1988, police reports show.

Since his ordination in 1966, he was shuffled to a dozen parishes and took a three-year leave of absence after his last arrest in 1988, diocese records state.

When the brothers came forward, the 64-year-old cleric was forced to step down as pastor of St. Anthony in Columbus Grove on Oct. 22 while the diocese investigates his past. Reached by phone recently, he declined to comment.

The case raises serious questions about whether church leaders protected and concealed a troubled priest - someone who ingratiated himself to a close-knit family, praying with them on holidays and celebrating their birthdays, say the brothers’ lawyers.

A Blade investigation of 24 clergy abuse cases in the Toledo diocese involving children between 1960 and 1994 shows the scenario is not unique.

In 18 cases, the alleged offenders were close to their accusers - students or altar boys - and in 12 of those examples, close to their families.

The Claars are like so many others in the church abuse scandal: They stepped forward because others were doing so.

"It gave me the courage. I guess I realized that I wasn’t alone," says William Claar, who is married and lives in Anchorage.

The trend began in Boston with the controversy of Cardinal Bernard Law’s coverup of pedophile priests, and spread rapidly.

In the Toledo area, 31 people - men and women - were interviewed by The Blade since June. Some cried, and some reacted angrily to memories they say were spawned as long as 45 years ago.

In six cases, victims said they were threatened by priests not to talk, and when they tried, they were met by indifference and sometimes, hostility by church leaders.

Toledo Bishop James Hoffman conceded the diocese did not always respond appropriately to victims in the past, and naively transferred priests who were accused of molesting youngsters to different parishes.

But the 70-year-old spiritual leader said the diocese has gained a deeper insight into clerical abuse, and now embraces zero tolerance.

He said he has met with numerous victims, and has encouraged many to undergo counseling at church expense.

"I always start out by apologizing to the victims for what happened to them," he said in a recent interview. "I just know that if we don’t respond and reach out to victims, that we haven’t done our job."

The bishop, who took office in 1981, said no known incidents of abuse have been reported since the diocese adopted a 1995 policy on sexual abuse.

But even after the policy was enacted, church leaders failed to keep promises to monitor an accused abuser, and in another case, to remove a priest from ministry until The Blade revealed his role on a church tribunal in August.

Twice this year, congregations were misled about their priests’ abuses until the stories were reported by the media.

Church leaders so far have refused to open their secret archives of sexual abuse to the public, but after a two-month delay, they allowed the Lucas County prosecutor to begin reviewing the files on Oct. 15.

Thirteen abuse lawsuits have been filed against the diocese since April, with nine of the cases asking the diocese to open sex misconduct files. Similar legal challenges led to the public disclosure of the Boston archdiocese’s archives in 2001.

Toledo attorney Catherine Hoolahan, left, SNAP President Barbara Blaine, and attorney Jeffrey Anderson file lawsuits. Photo by the Blade / Andy Morrison.

Trembling hands

On a bright July day, Harold Lee stepped away from reporters near the Lucas County courthouse, crouched under a shade tree, and lighted a cigarette.

His hands trembling, he couldn’t bear to hear his lawyers talk any more about the former Toledo priest who molested and abused him as a child.

Forty years earlier, he had told his parents and the local prosecutor that the Rev. Leo Welch was sexually abusing him and other boys at a cottage near Lake Erie.

The prosecutor didn’t prosecute. The parish pastor dismissed the story. And the crimes were quietly covered up.

Now, the truth was finally being told at a news conference announcing his lawsuit - two weeks after the former priest admitted "crossing the line" with altar boys in what he called "sexual experimentation."

But for Mr. Lee, 51, the anguish had never subsided.

His case is like so many others emerging since the church crisis exploded this year: He kept silent for decades, too ashamed to talk about his loss of innocence to a man who stood on a holy pedestal.

Unlike many victims, he spoke up right away, but nothing was ever done.

Like half of the 32 victims interviewed by The Blade, Mr. Lee turned to substance abuse as an adult. And in his case, it was alcohol.

Even though he was a plaintiff in a lawsuit, he still struggled with his long-buried emotions at the July 15 news conference.

As the church crisis continues - with more than 300 priests across the country removed from ministry this year - social scientists say they are just starting to understand the complexities of sexual abuse of children by clergy.

For decades, the issue was buried deep in the internal files of the Catholic Church, a subject rarely discussed by society.

Further concealing the problem was the obvious: Victims were reluctant, afraid, or unable to talk about being violated by those whom they believed to be Christ’s representatives on earth.

"We were taught to look up to priests, and to obey them," said Mr. Lee, who lives in Roanoke, Va.

Clerical abuse of children represents 2.8 percent of sex crimes in the country, said Dr. Bernard Cullen, a Medical College of Ohio professor who sits on the diocese’s abuse study committee.

But the psychological damage inflicted by clerics has caused suicides, post-traumatic stress, and severe depression, he says. Many experience a loss of faith and have rejected the church.

For years, Barbara Blaine blamed herself.

"I thought I had sinned. I went to confession. I wanted to get on with my life," says the 47-year-old lawyer.

But she always felt different, she says, and was always "feeling alone."

Her own struggles began in Toledo when, she says, she was sexually abused by a local priest, Chet Warren, starting at age 13.

"He told me that our love was from heaven," she says, "and it was blessed as a gift from God."

She went to Toledo church officials in 1985, who failed to respond to her pleas to remove the priest from ministry, letters and records show.

She said the priest’s religious order, the Oblates of St. Francis de Sales, and the Toledo diocese, told her that she was the first to complain about Father Warren, a popular priest who helped many people.

But when she divulged her story to The Blade in 1992, more women contacted her and church leaders to say they were molested by the priest in what became the area’s first clerical abuse scandal. "I was validated after that," she says.

After hiring a lawyer, Ms. Blaine learned the church had been aware of problems with Father Warren for years.

In fact, 14 years before she reported her abuse, a woman sent a letter to church officials saying she was sexually abused by the priest, said Ms. Blaine.

Another woman, Shelley Killen, said she was sexually abused by Father Warren in 1973, and went immediately to his superiors. She now sits on the diocese’s abuse review panel.

Teresa Bombrys, 41, sued the ex-priest and his religious order in April, saying she was abused from 1970 to 1974 - the first of 13 abuse cases against the local church this year.

In the end, Ms. Blaine received a confidential settlement, and the priest was later stripped of his collar.

But she didn’t stop there: She founded what became the nation’s largest victims’ advocacy group, SNAP - Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests - in Chicago.

A mission to kill

After drinking beer and smoking marijuana in 1989, a former Central Catholic High School student says he packed a shotgun in his car one night and sped away. His destination: Crystal Lake in Michigan’s Irish Hills.

His mission: to kill the man that he says raped him - former priest Dennis Gray.

But the former student says after arriving at the cottage 60 miles north of Toledo, "I just couldn’t bring myself to do it. I couldn’t pull the trigger."

Now, 13 years later, the 32-year-old man says he found another way to try to bring closure to his years of struggling with abuse.

He filed a lawsuit Sept. 18 against Mr. Gray and the diocese in Lucas County Common Pleas Court, saying he was assaulted by the priest in what his lawyers are calling a "sexual frenzy."

Eight others have since sued the former Central religion teacher, accusing him of raping them in rectories and at his cottage. All except one, Matt Simon, 33, are using the name John Doe.

Mr. Gray, 54, who recently lost his dean’s job at Toledo public schools after The Blade revealed his troubled past in September, has denied the accusations, saying the accusers are after his money.

But diocesan records say otherwise. In a 1995 letter to an abuse victim, the Rev. Raymond Sheperd, vicar for priests, wrote that the onetime priest "admitted to us that he was guilty of child abuse. He is remorseful, and wishes to apologize.

"He has gone through two different courses of psychotherapy treatment since he left the priesthood."

The man who wanted to kill Mr. Gray says he was once so depressed about what happened to him - from the age of 14 through 17 - that he wanted to commit suicide.

Over and over, the priest took him into his bedroom at the cottage and raped him, saying it was "normal," and that it was for his own good, the lawsuit says.

Sometimes, the alleged abuser would berate the youth, and at one point, struck him on the face.

"His whole thing was putting you down, making you feel so low," says the alleged victim. "He wanted to control you - every part of you."

The victim spent years in counseling, and turned to drugs and alcohol at 17. "I can never begin to tell people how depressed and scared I was."

He said he felt further betrayed because the onetime priest, who gave up his collar in 1987, was a family friend.

"He knew my parents," says the former Central student whose mother went to Father Gray in 1984 and asked him to counsel her son. "He was supposed to make me become a better person because I was getting into trouble."

The 54-year-old woman says her son broke his silence and told her about his anguish in 1995. "It answered so many questions, and at the same time, it broke my heart. I knew all along something had happened to him," she said. "He was restless and angry for so long."

The mother says she feels guilt because she encouraged her son to join Father Gray at his cottage beginning in 1985. She was like many other parents of victims, who were honored that their son was spending time with a priest.

"It was a much more innocent time," said Dr. Joel Kestenbaum, a Rossford psychologist who treats child abuse victims. "Parents would be so pleased that a priest would take an interest" in their child.

When mothers warned their children about strangers, they never envisioned the predators wearing collars.

Parents told their children to "look out for that stereotyped guy: driving a battered vehicle, drooling, wearing grimy clothes," he said, "but not the guy who gave mom and dad communion last Sunday."

Connie Davis alleges in a lawsuit against the diocese that she was a resident of St. Anthony Orphanage when she was fondled by the late-Msgr. Michael Doyle. Photo by the Blade / Jeremy Wadsworth.

The same question

People who were abused by priests are often confronted by the same question: Why don’t you just get over it?

It happened so long ago.

Psychologists who treat victims say the effects are deeper and more insidious than most traumas and afflictions - and among the least understood.

A child molested by a priest experiences an array of emotions that trigger such coping mechanisms as suppression, denial, and anger - often concealing the real origin of their inner wounds, says Toledo psychologist Chris Layne, who has treated abuse victims.

"I filed it away by slamming it in a cabinet, locking it, and throwing away the key," says William Claar.

Like other male victims, he blamed himself, questioning his own sexuality, and keeping his secret from those closest to him. "I had all these thoughts: Was I gay? Was I normal?"

Compounding their inner struggles was that their perpetrators were part of a powerful - and revered - institution that concealed the problem for decades, says church sociologist A.W. Richard Sipe, of La Jolla, Calif.

Many victims grew up not even knowing the source of their pain. For Connie Davis, it was during a counseling session in 1997 when she finally broke down.

After two failed marriages, bouts with alcohol and drugs, and years of denial, the images of Msgr. Michael Doyle wouldn’t disappear, she says.

"All of a sudden, I was shaking. I started crying," says the 56-year-old woman.

She says her abuse at St. Anthony Orphanage began when she was 8 years old in 1954, when the now-deceased priest called her into his office, ordered her to sit on his lap, and slipped his hand under her panties, her lawsuit alleges.

It was the first of many sessions that took place until she was removed from the facility at age 12 for telling the nuns about the secret sessions, her lawsuit alleges.

But this wasn’t just any priest. This was Monsignor Doyle, a noted Toledo political figure, labor mediator, and social service advocate whose name appears on a wing of the diocese’s headquarters.

"I was slapped when I told them," she says.

Four decades later, one of her demands to the diocese is to remove the late cleric’s name and portrait from the church’s headquarters.

The case is particularly thorny for two reasons: the cleric died in 1987 at the age of 88, and the accuser’s half-sister has since told the diocese she was unaware of her sibling’s alleged abuse.

But since Ms. Davis’ lawsuit on Oct. 18, two other women have emerged to say they too were molested by the prominent cleric at the orphanage between 1954 and 1959 - with one of the accusers under treatment by a psychologist, say SNAP coordinators and lawyer David Zoll.

"Connie Davis was never alone," says Mr. Zoll.

Since the church crisis began this year, the local victims who have stepped forward vary in age, background, and stage of healing, but they’re united in their sense of betrayal. For some, the anger endures.

"It’s not about priest-bashing, because most priests are good people, and we shouldn’t lose sight of that," says William Claar.

"This is about pedophile priest-bashing. This is about exposing priests who should have been exposed a long time ago."

______________________________________

Part 3: Church Struggles to Quell Crisis

Church Struggles to Quell Crisis

Some safeguards fail to be implemented

By Michael D. Sallah and David Yonke

Toledo Blade

December 1, 2002

Toledo priests have met for years behind closed doors to share ideas about consoling the dying, the addicted, and the grieving members of their flocks.

Now, they gather to console themselves.

In support groups organized by the diocese, one says he was insulted by a shopper in a department store. Another says a young mother gathered her children as he walked by.

The Rev. Jim Bacik says the church needs to accept responsibility for the actions of its priests and bishops. Photo by the Blade.

The perceptions of American priests are dramatically changing, many of the clerics agree.

But what they are unable to agree on is how to fix a problem that has led to legal challenges, protests, and revelations that have stunned everyday Catholics since the child sex-abuse scandal exploded this year.

Indeed, the Toledo diocese still struggles to meet the demands of a crisis that has been brewing in the institution for decades, a Blade investigation shows.

For example:

* When victims step forward to talk about their abuse, it can take three weeks or longer to meet with the diocese's lone case worker, causing some to hire lawyers out of frustration, they say.

* While the diocese created a policy in 1995 to set up pastoral teams to work with victims, the panel was never formed - leaving the only case manager to juggle those duties for the last seven years.

* The policy also called for an investigative team to study abuse cases, but in seven years, it never met, diocese officials say.

* The diocese lacks an effective system to monitor sexual molesters removed from ministry - which led to two recent situations in which abusers were allowed to work directly with children.

"There are no cops on the beat," says Claudia Vercellotti, the coordinator of the Ohio chapter of Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests.

"You have a lot of heart beating and pontificating, but you really don't have a system, or mechanism, to respond and deal with the follow up and supervising to make sure this never happens again."

Though no known incidents of sex abuse have occurred since 1995, the diocese continues to reel from a spate of lawsuits and complaints filed in the last eight months from events between the 1950s and early 1990s.

Twice local church leaders adopted policies - in 1988 and 1995 - to cope with allegations and deal with the moral and legal challenges of a burgeoning problem. But many of the safeguards and guidelines were never carried out.

That doesn't mean the diocese doesn't talk to victims in distress.

For years, Toledo Bishop James Hoffman has met with people who say they were abused, often providing counseling at church expense.

"I just know that if we don't respond and reach out to victims, that we haven't done our job," he said in a recent interview.

But a long practice of secrecy in abuse cases - guided by diocesan lawyers - continues to pose problems for the local church.

Consider the case of Herbert Richey, Jr.

When the former priest was accused of sexually abusing young boys in the 1980s, the diocese resorted to a familiar practice: It settled the cases confidentially for undisclosed amounts of money.

The Crestline, Ohio, native took a leave of absence starting in 1992, records show.

A few years later, he quietly returned to the diocese as an organist and musical director at Toledo's St. Michael the Archangel Church, where he worked from 1994 to 1996 - in some cases with children at a nearby school.

The flock was never told of his troubled past.

He later left the parish and eventually turned up as an organist at a Trenton, Mich., church as recently as this summer.

He is now a substitute organist with the Detroit archdiocese, traveling to churches where he is needed, said a representative. When reached by The Blade, he refused to comment.

Bishop Hoffman says the diocese settled out-of-court cases on behalf of Mr. Richey, 52, but declined to elaborate, saying the agreements were confidential.

After Father Robert Thomas was arrested for having sex with a teenage boy in 1984, he eventually transferred to Arizona in 1986.

Bishop Hoffman said he told the Tucson diocese about the priest's conviction at the time, but the move was approved.

For 16 more years, the cleric served as a parish priest.

When a Blade reporter called the Tucson diocese in May, a spokesman said Arizona church leaders were surprised to learn of his arrest because there were no reports in their files of the Toledo case.

The 71-year-old priest was immediately suspended and has since been pulled from ministry.

The case is an example of why the church needs a better system of checks and balances to monitor priests with troubled pasts - regardless of whether they have been "reformed," say people studying the problem.

Part of the answer is to remove the secrecy that has shrouded the church for so long and to improve communication between dioceses.

In an effort to correct such breakdowns, the American bishops in June ordered local dioceses - including Toledo's - to bring in lay members to open the process of investigating abuse cases.

Last month, the diocese appointed a six-member lay board to review sexual misconduct cases and make recommendations to the bishop.

How the panel performs its duties could determine whether the diocese prevents further crises, say experts studying the problem.

One of the first orders of business comes Thursday when it hears the case of former seminarian Jon Schoonmaker, who claims he was abused by a Toledo priest when he was a teenager.

While the Dallas charter imposed tougher national guidelines on U.S. church leaders, each diocese has a great deal of autonomy in interpreting and enforcing those rules.

For instance:

* The Boston archdiocese is setting up a special panel to supervise clergy removed from the ministry.

* In Baltimore, the archdiocese published the names of 56 accused priests on the Internet to help ensure they do not end up in schools or parishes outside their areas.

"Exposure sometimes does more to prevent abuse than anything else," says David Clohessy, president of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests.

* In Dallas, a panel was created consisting of professionals in psychology and law enforcement to investigate sex abuse.

A major problem is that priests accused of sexual abuse are often forced from ministry without being investigated by police, thus their names do not appear on any sexual-offender lists to alert police or the public to their whereabouts.

In the Toledo diocese, which covers 19 counties, one priest is responsible for keeping an eye on clerics removed from ministry.

But since the 1960s, at least 12 priests have been stripped of their collars because of sexual-misconduct accusations - and eight still live in the diocese. Two live in southeast Michigan.

"Some of them could be ticking time bombs," says Bill Crosby, a Cleveland lawyer who represents several abuse cases in Toledo. "And ultimately, who is watching these guys?"

At the 577 Foundation in Perrysburg, the victims gather - some never giving their names, but always their stories.

Those who turn out for the support sessions run the gamut: from middle-age housewives to 30-something businessmen.

Their concerns vary, but the big issue that riles them: getting the attention of the Toledo diocese.

For those people who want to step forward, the diocese enacted a 1995 policy that calls for pastoral care committees to respond in 48 hours to victims. But seven years later, the teams are just now being formed.

George Keller recalls the frustration of wanting to talk to someone, but no one was there for weeks.

"I know for a fact I left three phone messages, and almost gave up. It took me three weeks to talk to someone," says the 53-year-old factory supervisor, who decided to voice his anger in March after years of living in silence.

He says he eventually met in April with the lone diocesan case worker assigned to the sex-abuse crisis: Frank DiLallo.

During the meeting, Mr. Keller says he talked about being repeatedly raped by former priest Leo Welch and expected the diocese to investigate his claims. He even met with Bishop James Hoffman.

The case manager called back, saying the diocese thought Mr. Welch was dead, and his files showed no abuse allegations.

But within hours, The Blade found the opposite: Mr. Welch was still alive and living an hour north of Toledo.

He was also willing to talk and made a startling confession: He sexually abused altar boys from Bellevue's Immaculate Conception Church in the 1960s, saying he was an alcoholic who lost control of himself.

Worse, he said he was caught in 1961, but the diocese never alerted police and quietly ordered him to undergo psychiatric evaluation.

After Mr. Welch's confessions were published in The Blade, Mr. Keller says he immediately went to a lawyer.

"I was stunned," he says. "At that point, I felt I had been lied to. I never wanted to see a lawyer. I don't like lawyers. But I wasn't going to be made into a fool, either."

He said he believes if the diocese had abided by their own 1995 policy and appointed an investigative team, "there's a chance they could have gotten to the truth, or at least took my concerns seriously."

Local SNAP leaders say Mr. Keller's experience "is typical of what victims have gone through," says Ms. Vercellotti. "We have several who never intended on filing lawsuits, but just got fed up.

"These are people who are already embarrassed about what happened to them. It's not like they're that crazy about coming forward in the first place. And the sad thing is, it wasn't about money."

Even Mr. Welch said he was surprised the diocese never called him.

"I ended up taking the liberty to call them," he said, and eventually, drove to Toledo to meet with Bishop Hoffman.

The diocese does not ignore victims, its leaders say, and it is now putting the pastoral and investigative teams in place.

Church leaders insist they were not needed until this year. "Our case manager took care of those concerns," says the Rev. Michael Billian, diocese chancellor.

Bishop Hoffman says he will continue to meet with victims, allowing them to talk publicly about their cases, even if confidential settlements are struck.

"We always ask whether we can help them with counseling or help them with pastoral care," says the bishop.

The national SNAP chapter praised the diocese for allowing its Toledo chapter to pay for a $200 advertisement to be published in the local church newspaper, the Catholic Chronicle.

The diocese is also gearing up - with its lawyers - to fight 13 abuse lawsuits filed this year in Lucas County Common Pleas Court.

While the legal challenges are being waged, other agencies outside the church are investigating ways to help prevent abuse by clergy.

For example, many prosecutors, police, and legislators are looking to close loopholes that have long benefited child abusers.

In Ohio, where the statute of limitations is six years, most crimes against children were not prosecuted because victims did not step forward until decades later.

But prosecutors in other areas of the country are now rethinking their tactics.

In Detroit, for example, four priests were indicted Aug. 27 for abuses that stem as far back as the 1960s. Wayne County prosecutors say they found an exception in the law that allows charges to be brought if a priest fled the state before the six-year statute ran out.

The Lucas County prosecutor's office has been reviewing the Toledo diocese's sex-abuse archives since Oct. 15 but has not made a decision to pursue any cases, which date back to the 1950s.

Toledo's SNAP chapter is lobbying for changes in Ohio law that would extend the timelines for filing charges in abuse cases.

They want laws modeled after California's, which has set up a one-year "window" starting Jan. 1 that lifts time restrictions - allowing prosecution of any past cases.

The success of the Toledo diocese's newly formed pastoral response and investigative teams will not be known for years, Toledo priests and lay leaders say.

Many disagree over key issues, including whether there should be full disclosure of abuse cases.

Almost all agree it is the greatest crisis in the 92-year history of the diocese, and with lawsuits pending, the full extent of past abuses has yet to be revealed.

In an important development, Lucas County Common Pleas Judge Frederick McDonald last month opened the way for sensitive testimony in an April lawsuit against former Toledo priest Chet Warren.

The judge refused to dismiss the case and said attorneys could interview church officials under oath.

The case - the first of 13 in the local sex-abuse crisis this year - accuses the defrocked cleric of sexually abusing Teresa Bombrys, now 41, starting when she was in the fourth grade.

Besides the legal challenges, the diocese still faces other issues.

Since the "zero-tolerance" policy was adopted in June, the Vatican and U.S. bishops last month approved giving church leaders discretionary power to keep repentant abusers in ministry - instead of expulsion.

The leadership of Toledo's longest-reigning bishop, James Hoffman, is in crisis since the 70-year-old cleric revealed two weeks ago that he has cancer.

The church has hired a leading public relations firm, Hart Associates, to help guide it through the current turmoil.

Many say the church has gone through crises before and will emerge stronger. But first it must rid itself of its own disease.

"We're undergoing this scrutiny because of the sexual abuse of priests and the bishops who have covered it up and not dealt with it properly in the past," said the Rev. Jim Bacik, theologian and pastor of Toledo's Corpus Christi University Parish.

"It's our fault, not the media's, and we need to accept the responsibility."